Folks refuse surrender. As I achieved a physique and acquired an attitude, a determination attended me; “Tom, never give in.” Post–high school wanderings brought a war; a war with everyone and everything. The main target: any representation of the establishment. Secondary targets? It really didn’t matter, I opposed every truth representing antagonist. Attitude is everything!

I wanted to grow my hair, as all the nonconformists did in my day and this meant moving out as kicked, because long hair didn’t fly in our house. I had learned how to smoke dad’s Pall Malls and developed it into dope smoking. Alcohol fetched comfort. I loved the feelings and freed inhibitions. Music serenaded my nodding and determined my weekend’s prowling, as girls also became a perpetual focus. I was a self-made man, Hardy har har.

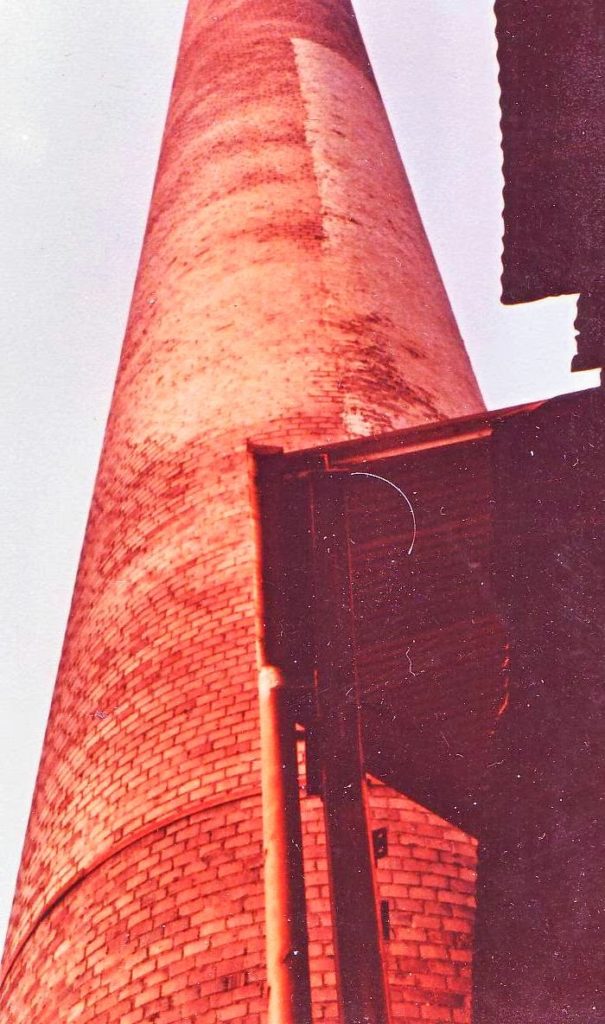

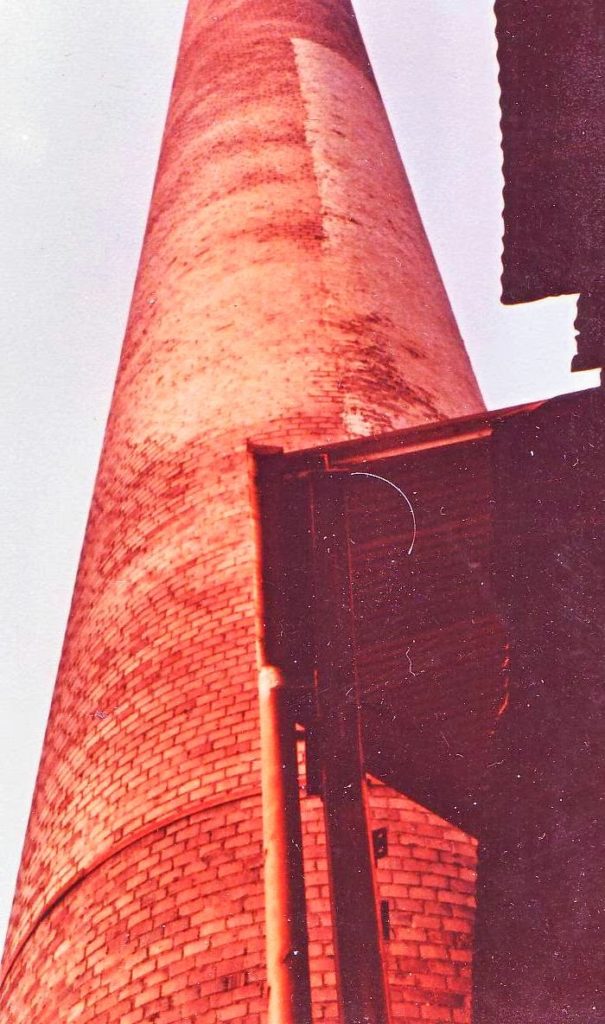

Steel mill introduced a Wonderland to us uninitiated. Mill reminded me of a Day-Glo poster; only without the glow. Filthy holes and pits, sometimes on hands and knees, stench to nausea, greeted us, and then hazed us into steel mill shape.

We shimmied in and out of tanks, boiler drums, and fireboxes; claustrophobic need not apply. We scoured slime pits, shoveled scale bins, and became masters at self–zipping those yellow astronaut suits. “Steam gun 101” was an actual classroom course and “universal solvent management” piggybacked that.

An assortment of masks and boots became our daily comrades, as tar and soot sullied our ankles, hands and nose hairs in that order. Coal dust and tiny cold chunks embedded themselves in our elongated hair. We learned the art of hair tying with scarves. Donning goggles and aprons and helmets and knee–pads; we worked and sweated. The odor of our own bodies’ factored in as the day went on.

After a few years we were able to bid on a job on a “line.” My first was in the “Hot Mill.” This line was about a football field in length and featured the making of a coil of sheet steel. The process went this way: first a solid red hot billet dropped out of the furnace onto the conveyor, bang! These were sometimes 10′ long by 5′ wide by 1′ high.

Immediately, that red-hot billet went through a machine called a scale breaker. Flaming pieces of metal flew in all directions as the conveyor moved that billet in and out, and back again. This part of the operation made the slab even redder hot looking, in spite of continual water spray. It next moved to the Rougher.

The Rougher consisted of two enormous rolls, one on top of the other, and accepting the flaming billet between them; one at a time could fit. This instrument would reduce that 1 foot thick piece of metal to about an inch, after several passes. The same rolling-pin effect elongated the chunk of steel to maybe 90 feet.

Finally, the forming steel sheet proceeded through six sets of rolls which reduced it to a quarter of an inch, give or take. This red steel entered a spool and wrapped itself up into a coil, and this is where my job began. Still red hot, that coil was dropped down onto a conveyor in front of me.

My job was to put a metal band around and clip to seal that hot coil, then write specifications on the side of it. I wore asbestos gloves, a mask, jacket and apron. A huge fan blew behind me to protect from the heat; I had to move quickly, however, as another was on its way!

Never did we savor the job, but it provided a paycheck, in spite of it all. We tolerated it to support the dope–head, carouser, sporty car buyer, pool–shooting, drunkard lifestyle with determination. We ran far from surrender and never got close enough to even care.

Crazy, but maybe I was that slab of steel. Reduction, reduction, reduction had a way of bringing me around. Surrender came eventually as life got hard. The rolls of life’s squeezing shaped me into a humble form. I am so thankful for the acceptance by God after it all. God’s plan culminated with me turning toward Him with no need for turning elsewhere. We are broken people. Amen!